Driving home one evening, “Clocks” by Coldplay came on the radio.

As an academic, classical music is beautiful to me for its tangible yet abstract architecture. This song by Coldplay (and many other pop songs) carries with it, however, an additional dimension less associated with classical music.

That dimension is the time and place it fell in my life. While I do love a good Mozart piano sonata, few Mozart sonatas have played along side my joys or sorrows. Brahms on the other hand…

I am not saying that classical music doesn’t accompany our lives in meaningful ways. Rather I am saying that there lies another dimension in the harmony of music that extends beyond the page and into the very events of our lives. And I am saying that pop music, because of its space in society, visits this dimension more readily.

When I hear “Clocks”, I hear notes, timbres, and rhythms.

But, when I hear the opening piano ostinato, I immediately feel elevated and drawn in:

Suddenly, I’m in the preview for the 2003 Peter Pan, in which I first heard this song, accompanying Wendy’s words that, (0:41)”never, is an awfully long time.” I think of the impermanence of life. I anticipate the magic of pirates and fairies. I am a child again. And I recall sharing this excited energy with my sister during the many treasured times we watched this film together.

Then, I hear the lyric: “Shoot an apple off my head.”

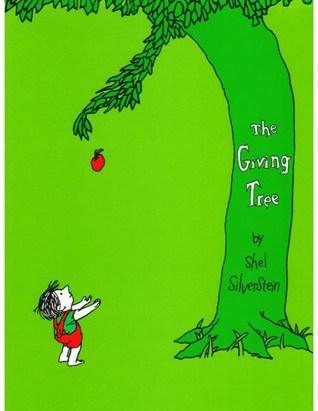

And I am again a child, listening to my dad explain the story of William Tell. I’ve just read Shel Silverstein’s poem of the same title from the collection Falling Up. And I see the image in the book and as my dad explains the story, I start to understand the humor. Somewhere in the background, an image of The Giving Tree emerges.

As the song continues, I have the sensation in my fingers of figuring out the piano ostinato. I’m sitting at the piano in our living room, and trying different pitches, reconstructing the sounds…

And I’ve notated it in a completely different key by mistake. And I receive the gift of music composition software for Christmas and create my own version of “Clocks” that modulates upward (“Second Star to the Right” on Melancholy).

The timbres from this track reemerge and add themselves to the “Clocks” on the radio. I put the track on my first “digital” album and give it to family members and a former teacher for Christmas.

The teacher tells me she used the track during creative writing time as ambient music for her students. And I’m back in her classroom, writing.

All of these memories and images swirl in a sort of vibrant, silvery-blue cloud that emerges from and envelops the “here-and-now” music. This music thwarts time, cheats it through another dimension. It creates Madeline L’Engle’s tesseract, bringing two different points in time into contact.

We’ll call “Clocks” Exhibit A.

Exhibit B is James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain”.

From the opening of the guitar intro, I’m 1 or 2 and it’s bedtime and my dad is rocking me to sleep in a pink rocking chair in the dim living room of our old house. There is a warmth to the dimness and I say, “Sing ‘Fire and Rain’, Dad”. And he sings. And I learn the words and sing along. Every image described in those lyrics lives in my memory still, as imagined then.

Then I’m 20 years old, in my second year of college. And I’m in a music practice room. And I’m trying to learn “Fire and Rain” on guitar or piano to play for my dad. … Then I’m 25, in a restaurant over spring break during grad school, and there’s live music. And the musician plays “Fire and Rain”. And I’m in all the places I’ve been with this song, plus, the “then-and-there” of that restaurant.

As a temporal art, music is powerful to transcend time. From 2 to 25, this song connects my childhood to my adulthood. Music transcends people, too. My dad and I will always share a love of this song.

Exhibit C is Brahms’ Op. 39, No. 15 Waltz in Ab Major.

I’ve always thought this particular waltz was pretty. When my fiance cut off our engagement, I decided it was time to learn it.

I’m back in a practice room, my metronome is set at 40. No, that is too fast. I’ll try 33 instead. Though I know Brahms is beyond me as a clarinetist who dabbles in piano, I’m going to learn this piece and I have enough pain to fuel the time to learn it.

The melody begins. It tells me, “There are times when Brahms is the absolute only answer to life.” My high school band director was right. He lost his wife to cancer. She is in a better place now. The register transfer in this piece gets me, every time.

Today, I learned that one of my students has suffered a great loss. I would like to dedicate this post to them. And to anyone who has seen their world torn away from them. Music, in the face of time, renders us equals: beautiful, temporary, transcendent.

Next: “Life Has a Soundtrack: ‘For the Beauty of the Earth’, Thomas Newman, and Shostakovich.”